Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel (Part 2)

Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel

(Part 2)

A good story is about a character who ACTS. His actions and decisions drive the story forward. However, many aspiring writers string together scenes that an editor might call ‘episodic.’

What is ‘episodic?’

This is when your character seems to enter a scene without a clear scene goal or intention of pursuing a scene goal, and a random event occurs causing the character to react. Then another disaster happens to this character in the next scene or the character gets more bad news. The character is like a leaf blowing in the wind trying to cope with one disaster after another. But what is happening is that the character is not the one driving the story. The character is in constant reaction mode.

Example:

A character is on her way to work and gets in a fender bender. Then while complaining to her boyfriend about her damaged car, she finds he has been cheating on her with another woman and wants to end their relationship. While crying about this latest hardship with her best friend over coffee in a crowded outdoor shopping square, a bomb goes off and several people are hurt, one of whom is the character’s dear uncle. The character does not know what to do next and looks to other people for advice. Or she may simply let someone else lead and make decisions for her.

Also, many times it seems as if ‘episodic’ scenes do not have anything to do with one another or the overall plot. They exist only to bring your character grief, which the author mistakenly thinks is ‘conflict.’

Think about a snowball fight. If a character keeps having to dodge snowballs being thrown at him, he will have no time to form and toss back one of his own. He is constantly cowering and ducking. Instead, the character should engage in a back-and-forth fight to overcome the opposition and achieve their story-worthy goal. If the antagonist throws a snowball (takes an action to thwart him), the character should then take action to throw one back. Back and forth. Your story needs to be balanced between Action and Reaction.

Even if your character does have a scene goal he attempts to pursue, your scene can still end up ‘episodic’ if the disaster at the end of the scene flies in from out of the blue and has nothing to do with the character’s struggle within that scene.

Example:

A top executive is having an intense argument with his boss over an ethics issue at work and the reader wonders if the executive will get the promotion he is seeking or if he will get fired. Then instead of answering this question at the end of the scene, the author has a tornado hit the building and suddenly the executive is in reaction mode trying to save himself or others from the wreckage.

Now, if this tornado has a direct connection to your plot and changes the executive’s goals, then I suppose it could work if it is a one-time event. Especially if it is at the beginning of your story acting as an Inciting Incident to start the character off on their story journey. But typically, the disaster at the end of a scene should come from the conflict within that scene—conflict that has already been set up.

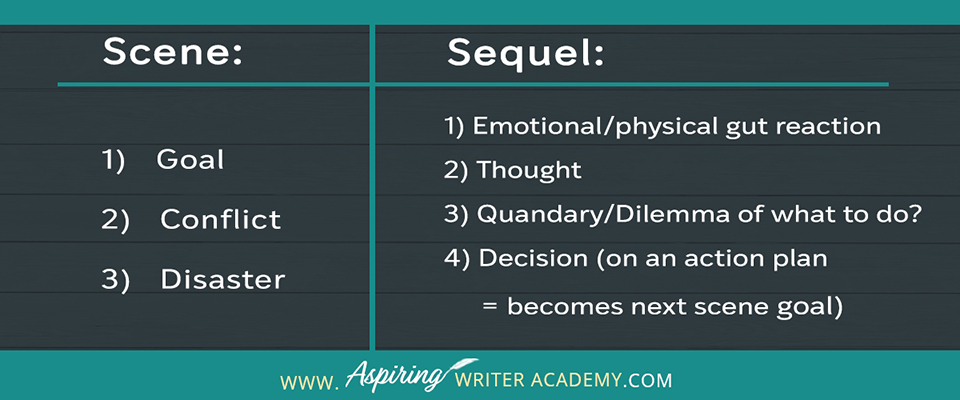

As already discussed in Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel (Part 1), using the components of Scene and Sequel will help you stay on track to write a story that keeps readers riveted from beginning to end.

If you are unfamiliar with the concept and components of Scene and Sequel, I highly suggest you read Part 1 of this post before continuing. For those who are ready to roll up their sleeves and get to work, let’s go!

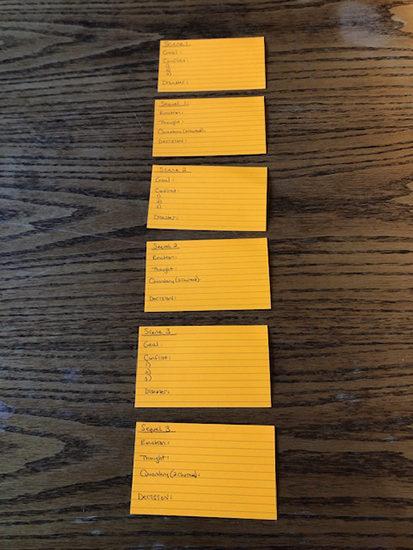

Exercise: Use Index Cards to Help You Plot

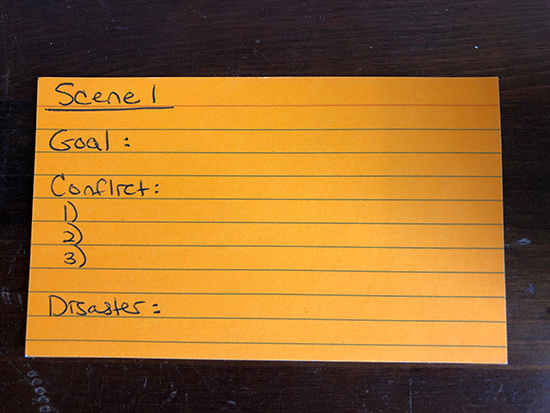

1. Take a stack of index cards and on the first card write: Scene 1 and vertically list the components (goal, conflict x 3, and disaster) that will make up that scene. Beside each component, list what will happen in this scene. You do not have room for complete sentences. Fragments are okay. Just a few words or a short sentence to list your ideas. This will help you focus.

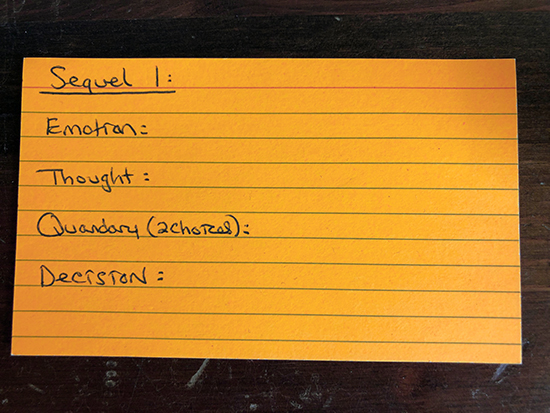

2. Then take another index card and write: Sequel 1 and vertically list the components (emotion, thought, quandary, decision) on that card that will make up the sequel and again, list your ideas for each one.

The Sequel is the reaction segment to the Scene before it. A good story will have both Scene and Sequel (ACTION & REACTION) segments. Sometimes the sequels will be brief, only taking up a line or two. Sometimes, for more emotional moments or for harder choices the character must make, you may slow down and draw out the components of the sequel in a full paragraph or several paragraphs. Longer sequels will of course affect the pacing of your story. Dramatic scenes tend to have more thoughtful, longer sequels. Fast-paced action-suspense scenes tend to have quick, shorter sequels. You, the author, need to decide what is best for your story.

I recommend that you use a different index card for the Scene and the Sequel because sometimes when working with multiple point-of-view characters, the sequel may not directly follow the end of the scene. Because each new character with a POV will have their own scene and sequel, you may need to braid the different storylines back and forth in a weaving pattern. You may choose to leave the reader at the end of one scene wondering what will happen to a specific character until he shows up again in the story and then show the sequel to the character’s scene that happened several pages before.

3. Now take two more cards for Scene & Sequel 2.

The decision the character made at the end of Sequel card 1 will become the new scene goal for Scene card 2. (Yes, you can literally write the exact same line.) Fill out each component for these cards like you did for the first set.

4. Next take 2 more cards for Scene & Sequel 3, fill out, and continue doing the same for Scene & Sequel 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and etc.

The key is to start at the beginning of your story when your character discovers he has a story problem (Inciting Incident).

Example: The character is informed by the bank that if she cannot bring her mortgage up to date within 30 days, she will lose her cupcake shop and they will lease the space out to her biggest rival.

The character will then need to formulate a story-worthy goal to overcome that problem to make his life happy again.

Example: The character vows she will pay off this debt and save her shop no matter what it takes!

This overall story goal should take several steps to attain. In other words, the larger story goal should be one that can be broken down into smaller steps (and many chapters) before it can be achieved. Picture a ladder. What are the smaller individual steps the character needs to do? What attempts can she possibly try to solve her problem and get what she wants? Brainstorm ideas and start the very first step this character should take to try to achieve their overall story goal. The first step will be the first ‘scene goal.’

Then Scene-Sequel-Scene-Sequel your way to the pivotal event at the end that allows your character to finally achieve success. Or not, if the character is meant to lose.

Spread these cards out on a table or floor and create a vertical line of your story from beginning to end. Instead of a straight line of Scene-Sequel-Scene-Sequel (which is fine, but may become predictable and boring), you may find you want to re-arrange the order as you weave in other character POV’s and story threads to create the best sequence to engage the reader. This might look something like Scene 1 – Scene 2 – Sequel 1 – Scene 3 – Sequel 2 – Scene 4 – Sequel 4.

Just remember that if you left a character off in a scene without an immediate sequel and go on to another scene, then the very next time you are back in that first character’s POV you need to start with his sequel to the scene where you last left him before plunging him into the new scene.

Yes, you can start a POV segment with a character going through the components of his last scene and then transition straight into his next scene with his new scene goal.

The hardest thing about Scene & Sequel is learning to write strong story hooks. The character’s scene-ending disasters and sequel-ending decisions of what to do next are what drive the story. (This) happens, so the character DECIDES to do that. And then because of that decision, this happens, and the character decides to do this next.

Look at each of your scene-ending disasters and each of the sequel decisions in your line-up of cards. Perhaps write them in a list on a separate piece of paper.

Scene 1 disaster –

Sequel 1 decision –

Scene 2 disaster –

Scene 2 decision –

Scene 3 disaster –

Scene 3 decision –

What do you see? Do these 2 components propel your story forward? Are they exciting? If not, you may discover you have some weak links that need strengthening. Dull, ho-hum decisions make for a dull story. Rev up the tension! Make the disasters even more dire, more personal to the character or his story world! Make the decisions and action the character takes more consequential. Do this, and you will pack even the quietest of stories with more power.

5. A few more tips for filling out the Scene & Sequel index cards:

- Use select words or fragmented phrases instead of full sentences for sharper focus.

- Fewer words are also easier to read at a glance.

- Scene Goals should start with a verb: Go to store, get bank loan, fly to Hawaii, convince father to allow me to work restaurant full time, sew a quilt, learn Spanish, strike a deal with the hero/convince him to help, prepare rooms for shipwreck survivors, feed the hungry crowd.

Is your verb strong enough? Instead of a character ‘Asking’ someone to do something maybe the verb could be ‘Demand’ or ‘Convince.’ But then we need to ask how does this character convince? Maybe the goal is: ‘Bribe’ or ‘trick’ someone into doing something. Strike a deal is also a good one. At the end of the scene, we see if the deal has been made or not. We can see if the bribe or trick worked. Strong verbs allow us to visualize the attainment of the scene goal. Use specific verbs on your index cards for a better, stronger scene.

- The Sequel’s Quandary: This is a choice between 2 specific things (not 4 or 5). Try to put your character between a rock and a hard place where no choice seems to be good. Which will the character choose? Example: Should she stay or should she go? Lie or go to jail? Accept the deal or lose everything? Fight or walk away? What are the consequences of each choice? How will they affect the character and their overall story goal?

- The Decision at the end of the Sequel: The decision is one of those 2 choices deliberated over in the quandary. If the dilemma was to either fight or walk away, then the decision might be to fight. You only need one word here – Fight. Although you also need to add how the character plans to fight. The character must come up with a specific action plan using the S.M.A.R.T. goal criteria. This is the next action the character will take – it will be her next scene goal.

- It is possible that a sub-plot may temporarily derail or take the character away from taking direct action on the decision they made in their last sequel. The character instead, may need to help a sub-plot character with their storyline first. This is where you wouldn’t necessarily change POV’s but have the main character pause his own quest for just a moment. (Maybe the cause of this necessitated pause was set up by the antagonist to thwart the main character’s plans!) But when the main character returns from that little adventure, he will pick up where he left off and go forward.

Laying out your Scene & Sequel cards is a lot of fun to do with a friend, class, or critique group. You can line up the cards on a table or on the floor. Or perhaps you can post them on a bulletin board. One writer I know covered a door with brown paper and taped on index cards to plot her novel from top to bottom.

If you use the Scrivener writing program, I believe there is a corkboard section that allows you to lay out your scenes. Or you may want to type your Scene-Sequel components into a word doc where you can cut and paste and move sections around if you find you need to edit.

Have fun with it! And if you need help, you can always contact us with a question at https://www.aspiringwriteracademy.com/contact

For further study into Scene & Sequel, you may want to add some of the following titles to your literary bookshelf:

Techniques of the Selling Writer

by Dwight V. Swain

Scenes and Sequels : How to Write Page-Turning Fiction

by Mike Klaassen

Writing Deep Scenes: Plotting Your Story Through Action, Emotion, and Theme

By Martha AldersonJordan Rosenfeld

How to Write a Dynamite Scene Using the Snowflake Method (Advanced Fiction Writing) (Volume 2) 1st Edition

by Randy Ingermanson

Scene and Structure

(Part of the Elements of Fiction Writing Series)

by Jack M. Bickham

The Craft of Scene Writing: Beat by Beat to a Better Script Kindle Edition

by Jim Mercurio

How To Write That Scene: Professional Techniques For Fiction Authors (Writer's Craft Book 28) Kindle Edition

by Rayne Hall

Make a Scene Revised and Expanded Edition: Writing a Powerful Story One Scene at a Time

by Jordan Rosenfeld

Do you find it difficult to create compelling antagonists and villains for your stories? Do your villains feel cartoonish and unbelievable? Do they lack motivation or a specific game plan? Discover the secrets to crafting villains that will stick with your readers long after they finish your story, with our How to Create Antagonists & Villains Workbook.

This 32-page instructional workbook is packed with valuable fill-in-the-blank templates and practical advice to help you create memorable and effective antagonists and villains. Whether you're a seasoned writer or just starting out, this workbook will take your writing to the next level.

If you have any questions or would like to leave a comment below, we would love to hear from you!

ENTER YOUR EMAIL BELOW

TO GET YOUR FREE

"Brainstorming Your Story Idea Worksheet"

7 easy fill-in-the-blank pages,

+ 2 bonus pages filled with additional story examples.

A valuable tool to develop story plots again and again.

Our Goal for Aspiring Writer Academy is to help people learn how to write quality fiction, teach them to publish and promote their work, and to give them the necessary tools to pursue a writing career.

Other Blog Posts You May Like

Writing Fiction: How to Develop Your Story Premise

12 Quick Tips to Write Dazzling Dialogue

10 Questions to Ask When Creating Characters for Your Story

Macro Edits: Looking at Your Story as a Whole

Basic Story Structure: How to Plot in 6 Steps

Writing Fiction: How To Keep Track of Time in Your Story

Behind the Scenes: Interview with the Authors of the “Sew in Love” Collection

is a multi-published author, speaker, and writing coach. She writes sweet contemporary, inspirational, and historical romance and loves teaching aspiring writers how to write quality fiction. Read her inspiring story of how she published her first book and launched a successful writing career.