Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel

Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel

(Part I)

Ever feel ‘stuck’ while writing or had your story called ‘episodic’ or ‘unmotivated?’ Do you have a hard time moving your story forward in a way that grips the reader?

Learn the individual components of Scene & Sequel to structure your scenes, advance the plot, and increase the stakes with each character decision.

Using this technique while writing your story from beginning to end will not only up your chances of completing your manuscript but give you the tools to create a story that your readers will claim ‘they couldn’t put down!’

But before we get into the nitty-gritty of components, let us go over some basics.

What is Scene and Sequel?

According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scene_and_sequel, “Scene and sequel are two types of written passages used by authors to advance the plot of a story. Scenes propel a story forward as the character attempts to achieve a goal. Sequels provide an opportunity for the character to react to the scene, analyze the new situation, and decide upon the next course of action.”

When I was first learning the craft of writing fiction, I was introduced to Dwight V. Swain’s book titled, Techniques of the Selling Writer. Go to any writer’s conference and most published authors will all agree that this is truly one of the best resources for an aspiring author.

While some may say that the information that he includes is a bit overwhelming in its presentation, it is none-the-less a book I would highly recommend for any author who wants to pursue a successful publishing career.

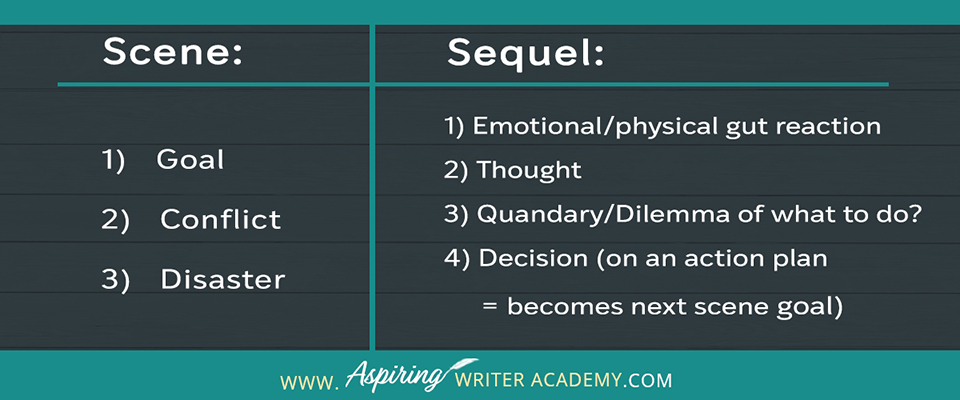

When referencing ‘Scene & Sequel,’ Dwight V. Swain is one of the first to define the individual components of a scene as: 1) goal 2) conflict 3) disaster. Sequel, as the unit of transition between two scenes, follows with: 1) reaction 2) dilemma 3) decision.

But what brought on that ‘lightbulb moment’ for me and made all of this really make sense, was when I studied a book by Jack Bickham titled: Scene & Structure (Elements of Fiction) where he explains in depth how to use each of these components. I would highly recommend that you also add this book to your reference library. While Swain’s book covers a multitude of advice on how to construct and sell a novel, Bickham focuses only on the structure of Scene and Sequels.

After learning the elements of Scene & Sequel myself, I created a template that I now use when I teach at various writer conferences. It is my sincere hope that you can learn from it as well.

Scene:

1) Goal: Have your character state or think their goal as clearly as possible within the first paragraph. This is not the overall story goal, or a fanciful desire, but a specific scene goal the character feels she must achieve right now to help resolve the overall story-worthy problem. One small step forward. When this goal is introduced at the beginning of the scene, it forms a scene question in the reader’s mind. Will the character achieve this goal? (They read on to find out!)

Not only do you need to have your character state or think their goal, but you need to show them pursuing this specific scene goal in action. What direct action does your character take to try to achieve this specific scene goal?

2) Conflict: What are 3 things that can bring opposition/conflict to that goal within this scene? Show 3 exchanges of push & pull action, or dialogue causing conflict. (Does the antagonist catch your main character in action and fight back? Or is it a confrontational argument?) By 3 exchanges, I mean 3 stimulus-response units within the scene. In dialogue or with physical action, this would be 3 separate back and forth tension-filled segments between two characters. (Don’t worry, I will illustrate below!)

3) Disaster: How does this end in disaster for the main character? How did their action or attempt to achieve their scene goal now make things even worse? Or how did it now make solving their story problem harder? The disaster provides the reader with the scene answer to the scene question. Did your character achieve their scene goal?

The scene answer should always be either:

- Yes, but—. The character gets what he wants but there are strings attached, consequences.

- No. The character hits a dead end and will need another plan.

- No & furthermore. No, the character did not get what he wanted, and now—because of his attempt—things are even worse than before!

Example:

Goal: The character goes to her first job in a restaurant (specific action) to help achieve her bigger story goal of earning enough money to buy a horse her opposition wants to put down. The overall story goal is very important to her, so this smaller scene-goal is equally important.

Conflict:

- The character arrives ready to work but the head cook says she doesn’t need another kitchen helper and refuses to let her in the door until she confirms with the boss.

- After confirmation, the character mixes up the ingredients while cooking and the head cook says she has to remake one of the main dishes.

- While remaking the main dish, the character accidentally burns the food or spills grease and starts a small kitchen fire infuriating the head cook, who again calls the boss.

Disaster: The character is fired, and furthermore, she now has to repay the owner for the damages she caused, which will set her back even further in earning enough money to buy the horse.

The Scene Question at the beginning:

Will the character succeed in her first day of work (to earn money to buy the horse?)

The Scene Answer delivered with the disaster:

No, and furthermore, she is even worse off than before with her finances.

If the character does not state or think about her scene goal and how important it is as she enters the scene, the reader does not know what the character hopes to achieve. Likewise, the reader does not know what to root for. And creating a bond with the reader is essential.

Without at least 3 units of conflict, the scene will not feel complete. It will not seem as if the character tried hard enough to achieve her scene goal. This leaves a scene feeling weak, as if something is missing. Perhaps the scene wasn’t worth including in the story after all.

Scenes that end without consequences or some kind of "disaster" do not move the story forward because the character remains unchanged, drifting in what they want to do or where they need to go next. The story falters.

Sequel:

1) Emotion: This is a reflex reaction the character cannot control. A knee-jerk gut reaction to the disaster that just happened. If the character was not hurt in a physical fight, then what new info can deliver that same kind of devastating blow? We always feel emotion first before anything else. Does the character do a double-take? Or does his chest tighten? Does his stomach turn queasy? Does he catch his breath? Does a horrific, strangling ache lodge in the back of his throat? Do his eyelids sting?

2) Thought: after the initial shock has worn off, the character will start thinking about what just happened. How dare that evil wretch say such a thing! Or—How could he do that to me? The character may indulge in a silent rant. Why did this happen?

While others may label the first component of a sequel as ‘Reaction,’ I separate this into Emotion and Thought because too many beginning writers will skip right over the emotional reaction (which is crucial) and start right in with the character thinking. But in doing so, the reader misses out on the physicality of how the character feels. Include sensory descriptions.

3) Quandary/Dilemma of what to do? The character’s thoughts must then turn toward rationalizing a solution. He may think – ‘What will I do now?’ Instead of coming up with multiple choices, it is best to narrow it down. Block out all other options for the character except for two choices. This makes the character’s quandary very clear. He can now either do this or that.

Both choices should each have consequences. In other words, they should not be easy. They should also be actionable. What is the next action step this character will now do to try to achieve his overall story goal?

A story will stall if the character is not given a solid choice. Tension ramps up higher if it is a hard choice. Whatever the character chooses will become his next scene goal. ‘S.M.A.R.T.’ goals are Specific, Measurable (obvious how it’s going), Actionable, Relevant (to the main story goal), and Time-bound (has a finish date.) Having your character stick up their nose and ‘decide’ they are never going to speak to the other person again is weak. Deciding to retaliate by blowing up the other person’s house on Newbury Street with dynamite at 6:00 pm on Saturday, February 12th is clear and distinct. Give your character two ‘S.M.A.R.T.’ choices, preferably sticking him ‘between a rock and a hard place.’ Two equally challenging options. He must choose one.

4) Decision: Your character needs to decide upon a new plan of action. He can't just ‘see what happens next and go with the flow’ or wait for someone else to do something or make a decision for him. The character must make a solid decision how he will next try to thwart the opposition and achieve his overall story goal. What next step can he take? This next step will be his next scene goal.

* Again, this is where a lot of stories flounder. If your character doesn’t come up with a new ACTIONABLE plan, your story will become muddled. Old problems or arguments may be rehashed but nothing new seems to be happening. The character just goes around talking to other people about his problems, but he doesn’t really do anything to move him closer to achieving his larger story goal. Then you, the author, may feel stuck and wonder what went wrong. You will need to go back and find where you lost your way. Strengthen that weak character decision. Strong stories have strong characters who make strong decisions!

The end of your scene-sequel sequence may have your character thinking about his new goal, stating his new goal to someone else, or he may already be in motion ready to pursue that new goal.

Example: Sequel to Scene 1 After being fired from her first day working at the restaurant:

Emotion: A tear slips down the girl’s cheek and her pulse flutters erratically inside her chest.

Thought: Fired? Didn’t the head cook see how hard I was trying? How dare she fire me! And I’m expected to pay for damages to the kitchen? Geesh! How will I ever afford to buy the horse now?

Quandary: The character can humbly crawl back to her previous employer at the warehouse and ask for her old job back—even though it was a job she hated with lower pay or summon the courage to work at the local veterinary clinic owned by her uncle—although she’d need to overcome her fear of needles and having to see sick animals put down. The latter choice also reminds her of her overall story-goal to buy the horse her opposition wants to put down.

Decision: She has already tried working at the warehouse and it didn’t give her the money she needed to try to reach her story goal. So she decides to courageously take on the job at the veterinary clinic owned by her uncle, even though she knows she will have to overcome some of her internal issues to work there. (The next scene will show her in action at the clinic trying to deal with those issues, which will be more challenging than she’d imagined.) Will she succeed in that endeavor? Or not? What will happen next?

The disasters at the end of a scene and the quandary / decisions at the end of a sequel often form the story hooks which keep your readers turning the pages. They form questions in the reader's mind. The reader is curious to see how the character will react and what he will do next.

How will the character feel when he learns the secret that has been kept from him?

What will the character do after getting dealt such a disastrous blow?

Which choice or option will they choose?

What will happen when the antagonist finds out what the main character plans next?

To ramp up the reader’s interest even further, make your last line in a scene or sequel a real zinger that surprises the reader or makes them laugh. Or throw them a plot twist they didn’t expect.

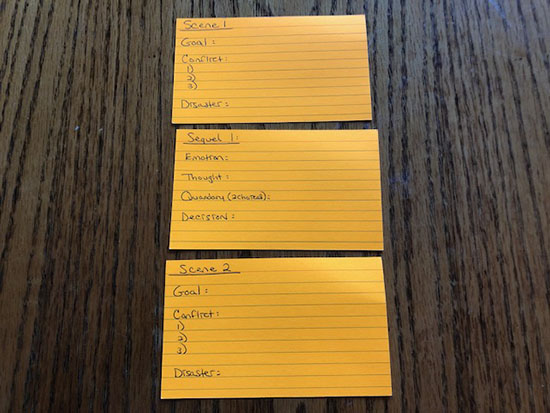

Exercise: Use Index Cards to Help You Plot

Take a stack of index cards and on the first card write: Scene 1 and vertically list the components (goal, conflict x 3, and disaster) that will make up that scene. Beside each component, list what you want to happen in this scene, just as I did in the examples above. You do not have room for complete sentences. Fragments are okay. Just a few words or a short sentence to list your ideas.

Then take another index card and write: Sequel 1 and vertically list the components (emotion, thought, quandary, decision) on that card and again, list your ideas for each one.

I recommend that you use a different card for the Scene and the Sequel because sometimes when working with multiple POV (point of view) characters, the sequel may not directly follow the end of the scene. Because each new character with a POV will have their own scene and sequel, you may need to braid the different storylines back and forth in a weaving pattern. You may choose to leave the reader at the end of one scene wondering what will happen to a specific character and continue on to a new scene featuring a different character. Later, when the character from the first scene shows up again in the story, you may then choose to show the sequel to the character’s scene that happened several pages before.

Now take two more cards for Scene & Sequel 2. And two more cards for Scene & Sequel 3.

Start at the beginning of your story when your character discovers he has a story problem that he needs to deal with to make his life happy again. Then Scene-Sequel-Scene-Sequel your way to the pivotal event at the end that allows your character to finally achieve success. Or not.

Spread these cards out on a table or floor and if you have multiple POV’s you may want to re-arrange the order to create the best sequence to engage the reader. Be sure to especially look at each Disaster and Decision. Does the story make forward progress? If not, you might discover you have some weak links that need strengthening.

Most important, have fun with it! Laying out your Scene & Sequel cards while brainstorming a story is a great activity to do with a friend, class, or critique group.

If you would like more resources to study Scene & Sequel, you may want to check out these books:

Techniques of the Selling Writer

by Dwight V. Swain

Scenes and Sequels : How to Write Page-Turning Fiction

by Mike Klaassen

Writing Deep Scenes: Plotting Your Story Through Action, Emotion, and Theme

By Martha AldersonJordan Rosenfeld

How to Write a Dynamite Scene Using the Snowflake Method (Advanced Fiction Writing) (Volume 2) 1st Edition

by Randy Ingermanson

Scene and Structure

(Part of the Elements of Fiction Writing Series)

by Jack M. Bickham

The Craft of Scene Writing: Beat by Beat to a Better Script Kindle Edition

by Jim Mercurio

How To Write That Scene: Professional Techniques For Fiction Authors (Writer's Craft Book 28) Kindle Edition

by Rayne Hall

Make a Scene Revised and Expanded Edition: Writing a Powerful Story One Scene at a Time

by Jordan Rosenfeld

Do you find it difficult to create compelling antagonists and villains for your stories? Do your villains feel cartoonish and unbelievable? Do they lack motivation or a specific game plan? Discover the secrets to crafting villains that will stick with your readers long after they finish your story, with our How to Create Antagonists & Villains Workbook.

This 32-page instructional workbook is packed with valuable fill-in-the-blank templates and practical advice to help you create memorable and effective antagonists and villains. Whether you're a seasoned writer or just starting out, this workbook will take your writing to the next level.

We Believe All Authors Can Aspire to Take Their Writing to the Next Level!

If you have any questions or would like to leave a comment below, we would love to hear from you!

ENTER YOUR EMAIL BELOW

TO GET YOUR FREE

"Brainstorming Your Story Idea Worksheet"

7 easy fill-in-the-blank pages,

+ 2 bonus pages filled with additional story examples.

A valuable tool to develop story plots again and again.

Our Goal for Aspiring Writer Academy is to help people learn how to write quality fiction, teach them to publish and promote their work, and to give them the necessary tools to pursue a writing career.

Other Blog Posts You May Like

Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel (Part 2)

Writing Fiction: How to Develop Your Story Premise

12 Quick Tips to Write Dazzling Dialogue

10 Questions to Ask When Creating Characters for Your Story

Macro Edits: Looking at Your Story as a Whole

Basic Story Structure: How to Plot in 6 Steps

Writing Fiction: How To Keep Track of Time in Your Story

Behind the Scenes: Interview with the Authors of the “Sew in Love” Collection

is a multi-published author, speaker, and writing coach. She writes sweet contemporary, inspirational, and historical romance and loves teaching aspiring writers how to write quality fiction. Read her inspiring story of how she published her first book and launched a successful writing career.

Thank you for the Brainstorming worksheet! Absolutely luv it. Makes me focus in on the important tasks. It is a well put together document. Having created several worksheets for my (nearly abandoned) novel, I can truly appreciate the time and effort that went into your worksheets’ creation. Can’t wait to put them to work. 🙂 You have interesting posts. Thank you, again.

Hi Penny, thank you so much for your sweet comments about our downloadable worksheets at Aspiring Writer Academy. We are thrilled that you found them helpful and will put them to good use. If you have any questions or ideas you would like to see in future posts, feel free to reach out. 🙂