Novel Writing Tips: Don’t Bury the Dialogue!

When writing the first draft of a fictional novel, authors may write fast, without giving much thought to format or style issues when it comes to dialogue. However, during the revision phase, it is important to look at each line to ensure the conversations between characters have the greatest impression upon readers.

In Novel Writing Tips: Don’t Bury the Dialogue! we show you how to make your character’s speech stand out for clarity, maximum impact, and stylistic effect.

Many aspiring writers have come away stumped after hearing an agent, editor, mentor, or critique partner say, “Don’t bury the dialogue!”

What does that mean?

It means the dialogue in your manuscript does not stand out to the reader. It is buried between lines of description, action sequences, and he said/she said tags. The impact of the words gets lost, having little effect on the reader.

Sometimes the dialogue between your characters is dropped into so much wordy clutter that the point of the conversation is unclear. Or there might not be a direct stimulus-response sequence, making it hard for the reader to follow.

In the post below, we will discuss:

- How to avoid sandwiching the conversation between description, action beats, & dialogue tags

- Tips to keep stimulus & response dialogue together for clarity and maximum effect

- Stylistic paragraphing strategies to strengthen impactful lines and scene-ending hooks

1) How to avoid sandwiching the conversation between description, action beats & dialogue tags

Scenes with only two people:

If you only have two people in the scene and you’ve distinguished your characters, either by their personality traits or differences in speech, then after an initial action beat or dialogue tag to identify the first speaker, you can have several lines of dialogue without anything else at all. Of course, you need to indent each line that has a different speaker to show who is speaking.

Example:

John gave her one of those soul-piercing direct looks which always put her on edge and let out a soft, low chuckle. “What do you think?”

“What do I think about what?” she demanded.

“Do you want to go with me to the dance?”

“I—I’m not sure that would be a good idea.”

“Why not?”

“For one thing, you’ve said yourself a million times, that you can’t dance.”

“I never said I can’t, but that I don’t usually care to.”

“Yet, you’re offering to dance now…with me?”

“If it means I get to hold you in my arms, yes. I will dance with you.”

Okay, you may think this example is a bit cheesy, but hey, I’m a romance author!

The point is that once you’ve established who is speaking, you can let the dialogue stand out on its own.

However, after about this many dialogue lines, I would include the character’s physical and emotional reactions in the next few lines with some description and dialogue tags before going into another section of straight dialogue.

You don’t want to go too long before re-establishing who is speaking, but can you see how this puts the focus straight on what is being said?

Scenes with multiple people:

If you have more than two characters in the scene, you need more identifiers to distinguish who is talking or the reader will get really confused. You might use a line of description, an action beat, or dialogue tags along with the line of dialogue for each character.

The key is to keep the dialogue either at the beginning or the end of the paragraph or segment to make it stand out and have more impact on the reader. Do not bury the dialogue in the middle.

Example of buried dialogue: between action beats

Sarah clenched her fists. “How dare you! What were you thinking when you drove my car without asking?” She stomped her foot and growled.

See how the dialogue is stuck in the middle? Let’s revise to let the dialogue stand out.

Sarah clenched her fists. Then she stomped her foot and growled. “How dare you! What were you thinking when you drove my car without asking?”

Now the reader anticipates the other character’s response with more intensity. What will be the very next line? How will the other character answer?

Example of buried dialogue: between dialogue tags

Lucy leaned forward and whispered, “What did Ellen say to you last night? You didn’t look like yourself afterward.” She shook her head. “In fact, your face turned paler than I’ve ever seen you, like you’d seen a ghost,” Lucy confided.

The problem with this is that the paragraph starts and ends with a dialogue tag. If you already have one dialogue tag, then that’s all that is needed. We know who is speaking.

Let’s revise to get this text cleaner and sharper. Decide which would be better: to keep the dialogue at the beginning or the end of the paragraph? I’m going to choose to establish the speaker and then keep the dialogue to the end of the segment.

Lucy leaned forward and whispered, “What did Ellen say to you last night? You didn’t look like yourself afterward.” She shook her head. “In fact, your face turned paler than I’ve ever seen you, like you’d seen a ghost!”

Now the reader can continue to the other character’s immediate response without a clunky dialogue tag in the way. There is no ‘pause’ with extra words in between.

Example of buried dialogue: between action beats and dialogue tags

He shifted his feet, unwilling to meet her gaze. “I didn’t think it was a big deal,” he retorted.

The problem is that the dialogue is buried between the action/body language and speaker tag (‘he retorted’) and doesn’t stand out. Keep the dialogue to one end of the paragraph or the other and be sure to keep most question and answers of dialogue back-to-back without interference.

If you have already established who the speaker is with the line ‘He shifted his feet, unwilling to meet her gaze,’ there is no additional dialogue tag needed. Dialogue tags only serve to identify the speaker. Show body language to show the emotion behind the words.

Or, if you do want to include a tag showing how the words were said, just be sure to keep it together with the action at one end of the paragraph or the other.

Better:

“I didn’t think it was a big deal,” he retorted. He shifted his feet, unwilling to meet her gaze.

Or

He shifted his feet, unwilling to meet her gaze. “I didn’t think it was a big deal.”

Example of buried dialogue: between a paragraph of description and more description (or transition/introspection segments

The ceiling in the main hall rose two stories high, allowing a glimpse of the mahogany rails of the upper loft on either side. Charles had played up in that loft many times throughout his youth, and the memories of the old train set his uncle had set up for him and his brothers to play with brought a pang of longing for the good old days. “Someday, the train set will be yours,” his uncle had said, although sadly, it never came into Charles’ possession. Where the train set had disappeared to, no one knew. From what he could figure, it might have been stolen long before his uncle’s demise.

From a reader’s viewpoint, they see this big block of text and their eyes want to skim right over it. The more open space on the page the better. Do not tire your reader’s eyes! Break this block up with additional paragraphing and draw out the dialogue as a focal point so the reader understands that what this character’s uncle said may be important to the character and the story.

Example of how this same text might be revised:

The ceiling in the main hall rose two stories high, allowing a glimpse of the mahogany rails of the upper loft on either side. Charles had played up in that loft many times throughout his youth, and the memories of the old train set his uncle had set up for him and his brothers to play with brought a pang of longing for the good old days.

“Someday, the train set will be yours,” his uncle had said.

Sadly, it never came into Charles’ possession.

Where the train set had disappeared to, no one knew. From what he could figure, it might have been stolen long before his uncle’s demise.

Visually, at a glance, it already looks better. The text has space to breathe. And now, by giving the uncle’s dialogue its own line, it clearly stands out and will be more memorable for the reader.

(I also gave Charles’ reaction to the dialogue its own line to stand out and to draw more emotion about how he feels about the situation.)

Example of buried dialogue: between a combination of description, action beats, and dialogue tags

That Saturday the storm increased, adding thunder and lightning to its arsenal. Most of the children hid in the alcove beneath the stairs, the safest place in the house—at least to their way of thinking. Mother had always told them that is where they should go if the house shook, and it was shaking harder than a wet dog after a bath. The rain pounded against the glass windows, the thunderous sound hurting his young ears and making him wince. He didn’t like rain. He clenched his small hands into fists. “When is it going to stop?” he shouted, tears streaming down his face. Would it ever stop? He turned to look at the other boy sitting beside him. By the boy’s expression it appeared he didn’t think so, which diminished his own hope as well. It wasn’t until he was much older, that he learned to welcome the storms and relish the times they’d spent together in that small, sacred, sheltered spot.

This big block of text is sure to put your reader to sleep! Is there really any dialogue in this paragraph? At first glance, you can’t even see it.

The text needs to be broken up. Try to leave as much “open space” on the page as you can so you do not give the reader a mental headache. Let the dialogue and direct thought lines (Would it ever stop?) stand out for maximum impact.

Better:

That Saturday the storm increased, adding thunder and lightning to its arsenal.

Most of the children hid in the alcove beneath the stairs, the safest place in the house—at least to their way of thinking. Mother had always told them that is where they should go if the house shook, and it was shaking harder than a wet dog after a bath.

The rain pounded against the glass windows, the thunderous sound hurting his young ears and making him wince. He didn’t like rain. He clenched his small hands into fists.

“When is it going to stop?” he shouted, tears streaming down his face.

Would it ever stop?

He turned to look at the other boy sitting beside him. By the boy’s expression it appeared he didn’t think so, which diminished his own hope as well.

It wasn’t until he was much older, that he learned to welcome the storms and relish the times they’d spent together in that small, sacred, sheltered spot.

Rule of thumb: Always keep the dialogue to the front or the back of a line or paragraph. This means absolutely NO words before or after it.

If the dialogue is “buried” between any combination of the elements above, it is time to revise so the words are clear visually (easy on the eyes) and easier for the reader to comprehend.

When the dialogue between characters is easy to follow, the pacing of the story picks up, allowing the reader to become immersed in the story without any distractions. Your reader will be able to fully understand and enjoy your story on a much deeper level.

2) Tips to keep stimulus & response dialogue together for clarity and maximum effect

One mistake many aspiring writers make is to place tag lines, action beats, and other clutter between one character’s question and the other character’s answer. By the time the reader sees the second character respond, they’ve forgotten the question. Too much time has elapsed. The impact is lost.

Try to keep all stimulus-response lines of dialogue together. If one character ends their paragraph with a question, have the other character’s paragraph start with direct lines of dialogue.

Example of too much clutter between the question and response:

Cassandra looked at the long list of chores scrawled on the notepad. “What do you think we should do first? Clean out the cellar or bake the cookies?” she asked, with a frown.

Her sister smiled and retrieved a baking tray from the pantry. “Let’s bake cookies!”

Now here is a much sharper, clearer stimulus-response segment:

Cassandra looked at the long list of chores scrawled on the notepad, then frowned. “What do you think we should do first? Clean out the cellar or bake the cookies?”

“Let’s bake cookies!” Her sister smiled and retrieved a baking tray from the pantry.

The only time you would not want to keep the question and answer (or stimulus-response) sequence together is if the second character wanted to intentionally stall, delay, or avoid answering the question. But in this case, it would be obvious to the reader that this is what the character is trying to do.

Example:

Mary placed her hands on her hips and scowled. “Did you take out the trash like I asked you to?”

Kyle picked up a pen and without making eye contact, he sketched the outline of a racecar on the bottom edge of his mother’s shopping list. “Uh… I’ll get to it later, after I talk to my buddy Joe.”

3) Stylistic paragraphing strategies to strengthen impactful lines and scene-ending hooks

If you have an important line of dialogue or a powerful line of thought from the character, you might consider dropping the line down into a new line of its own. Separate it away from the rest of the paragraph.

Not only does this create open space, but it forces the reader to focus in on that line. Often these lines act as “hooks” to draw the reader into turning the page and reading the rest of the story.

The drop-down line is for visual effect, heightened emotional impact, or to place emphasis on what is being said or what will come next.

Example:

Excerpt from The Groom She Thought She’d Left Behind (Part of The Runaway Brides Collection) by Darlene Panzera from Barbour Publishing:

(Emily and Gilbert have been working as servants, cleaning barn stalls, and it has not been easy. When their employer offers Emily a new position, she jumps at the chance.)

Emily agreed. “Thank you, Mr. Belmont. I would love to work in the kitchen.”

She meant every word, but as soon as Mr. Belmont left, Gilbert leaned toward her and whispered with concern, “Have you ever worked in a kitchen?”

“No, of course not,” Emily confided. “But after this, how hard could it be?”

After reading the above chapter-ending line, the reader highly suspects that working in the kitchen is not going to be as easy as Emily thinks it will be. The line acts as a hook to keep the reader turning pages. The reader will want to know what trouble Emily will find herself in next when she tries out her cooking skills.

If you raise a question (or plant a suspenseful image in the reader’s mind) with your scene-ending or chapter-ending hooks, the reader will want to know the answer. The reader will want to know what happens next. They will not be able to sleep at night until they turn the page and continue to read on, in hopes of finding out. That is the secret to creating a page-turner.

What is the best line of dialogue that your character can say to increase the intensity of the story by hinting at danger or trouble to come?

Below, is another example from that same story.

(The hero and heroine are supposed to be working as servants at a masquerade ball but are hiding in the coat closet, hoping they will not be recognized after they discover someone from their past among the guests in attendance. While whispering to one another, they realize they are falling for one another and are speaking about ‘love.’)

Excerpt:

The word hung between them, pulling them even closer together. . .

Until Stephen Belmont burst into the coatroom.

Raising his brows, their employer gave each of them a startled look, then his hushed voice spat, “What the devil are you doing here?”

Of course, if you had read the story from the beginning, you would understand that there are other hidden agendas at work in this scene that make it even more intense. But by ending on this “hook line,” the reader knows the couple who didn’t want to be found has been caught by someone who can cause even more trouble for them.

Hopefully, the reader will want to know what happens next after this pivotal moment and turn the page to read the next chapter!

For even more tips, you may also want to see our post, 12 Quick Tips to Write Dazzling Dialogue:

We hope you have enjoyed Novel Writing Tips: Don’t Bury the Dialogue! and that you have gained some valuable tips to create clear, effective conversations between your characters which will impact the reader.

If you have any questions or would like to leave a comment below, we would love to hear from you!

And if you would like additional help developing your story idea, we invite you to download our Free Brainstorming Your Story Idea Worksheet.

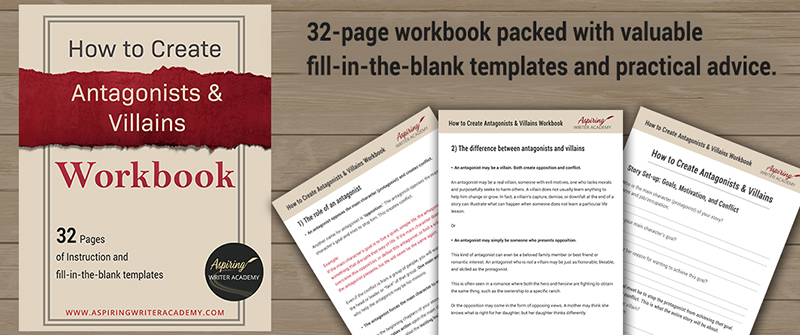

Do you find it difficult to create compelling antagonists and villains for your stories? Do your villains feel cartoonish and unbelievable? Do they lack motivation or a specific game plan? Discover the secrets to crafting villains that will stick with your readers long after they finish your story, with our How to Create Antagonists & Villains Workbook.

This 32-page instructional workbook is packed with valuable fill-in-the-blank templates and practical advice to help you create memorable and effective antagonists and villains. Whether you're a seasoned writer or just starting out, this workbook will take your writing to the next level.

Our Goal for Aspiring Writer Academy is to help people learn how to write quality fiction, teach them to publish and promote their work, and to give them the necessary tools to pursue a writing career.

ENTER YOUR EMAIL BELOW

TO GET YOUR FREE

"Brainstorming Your Story Idea Worksheet"

7 easy fill-in-the-blank pages,

+ 2 bonus pages filled with additional story examples.

A valuable tool to develop story plots again and again.

Other Blog Posts You May Like

Fiction Writing: Critique Group Etiquette & Warning Signs of a Good Group Gone Bad

How to Prep for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month)

Fiction Writing: How to Plot a Story where the Antagonist is an ‘Invisible Foe’

Fiction Writing: How to Find a Critique Partner/Group

How to Research Information for a Historical Novel

7 Steps to Begin Writing a New Fictional Story

Learn to Plot Fiction Writing Series: Story Analysis of the movie “Signs”

Fiction Writing: How to Get a Literary Agent

How Writing Prompts Can Improve Your Fictional Story

Creative Writing: 5 Ways to Strengthen a Weak Fictional Character

Fiction Writing: Create a Storyboard to Map Out Your Scenes

Fiction Writing: How Specific Details Can Bring Your Setting to Life

5 Common Mistakes New Writers Make

Fiction Writing: Story Analysis of the movie “Passengers”

Fiction Writing: How to Write Compelling Dialogue

Fiction Writing: 5 Key Differences Between a Novel and a Novella

Pros & Cons of Traditional vs. Self-Publishing Fiction

3 Ways to Avoid Writing ‘Episodic’ Scenes in Fiction

Scene & Sequel: The Secret to Plotting an Epic Novel (Part 2)

is a multi-published author, speaker, and writing coach. She writes sweet contemporary, inspirational, and historical romance and loves teaching aspiring writers how to write quality fiction. Read her inspiring story of how she published her first book and launched a successful writing career.